Crafting a Life: A Maker’s Journey of Transformation, Loss, and Wholeness

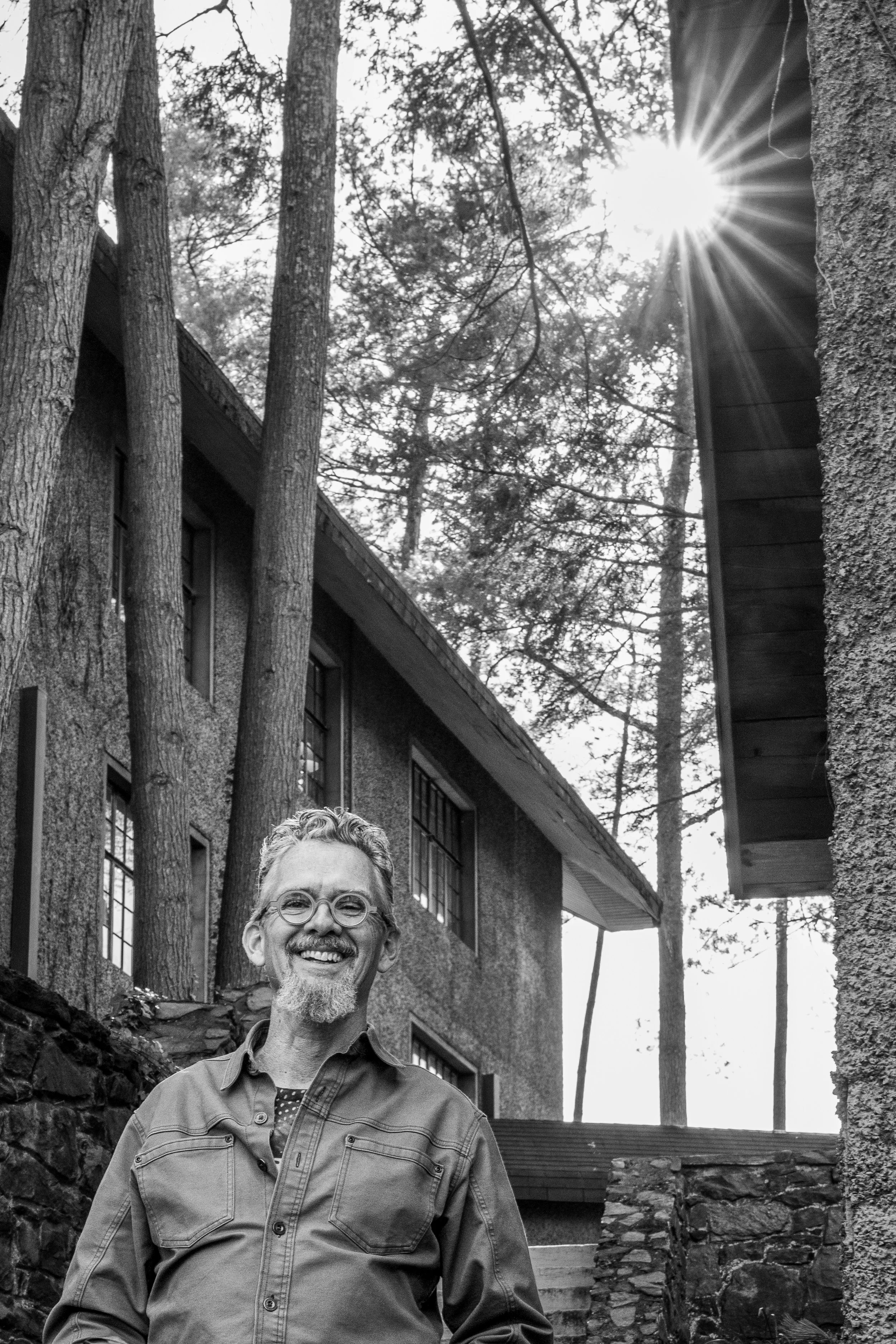

Brent Skidmore, Maker, Educator, Mentor and Bridger Between Worlds.

I first met Brent Skidmore during a rites of passage weekend with my then 13-year-old son. Brent stood out among the fifty men volunteering to hold space for young boys on their initiatory journey; his calm, grounded presence and deep conviction made an immediate impression. We crossed paths over the years, and he immediately came to mind as I was making a list of people to interview for this Portraits of Purpose series. As with all of these interviews, I listen for the “red thread” of purpose that weaves through each story, along with the internal and external energies that shape one’s path toward a life of loving service—to oneself and others.

Sitting with Brent in his workshop, surrounded by woodworking machines, tools, and furniture-making templates, I began to see how deeply his artistry reflects his life’s journey. The variety of mirrors on the wall, with their unique, organic shapes, reflected different portals into his life. Yet, capturing the whole essence of the man in the mirror remained elusive. His mind and heart seemed like impeccably crafted drawers, each containing a mystery, an adventure, a heartbreak, or a revelation waiting to be unlocked.

Brent is a natural storyteller whose narratives unfold with the same fluid beauty as his bespoke furniture and sculptures. His stories are rich with color and depth, reflecting his vulnerability as he questions and draws meaning from his life experiences. Like his woodwork, his stories lack straight lines and right angles; instead, they’re filled with unexpected turns and unique angles. But they always invite you to lean in, offering glimpses of something new and emergent from his deep imagination.

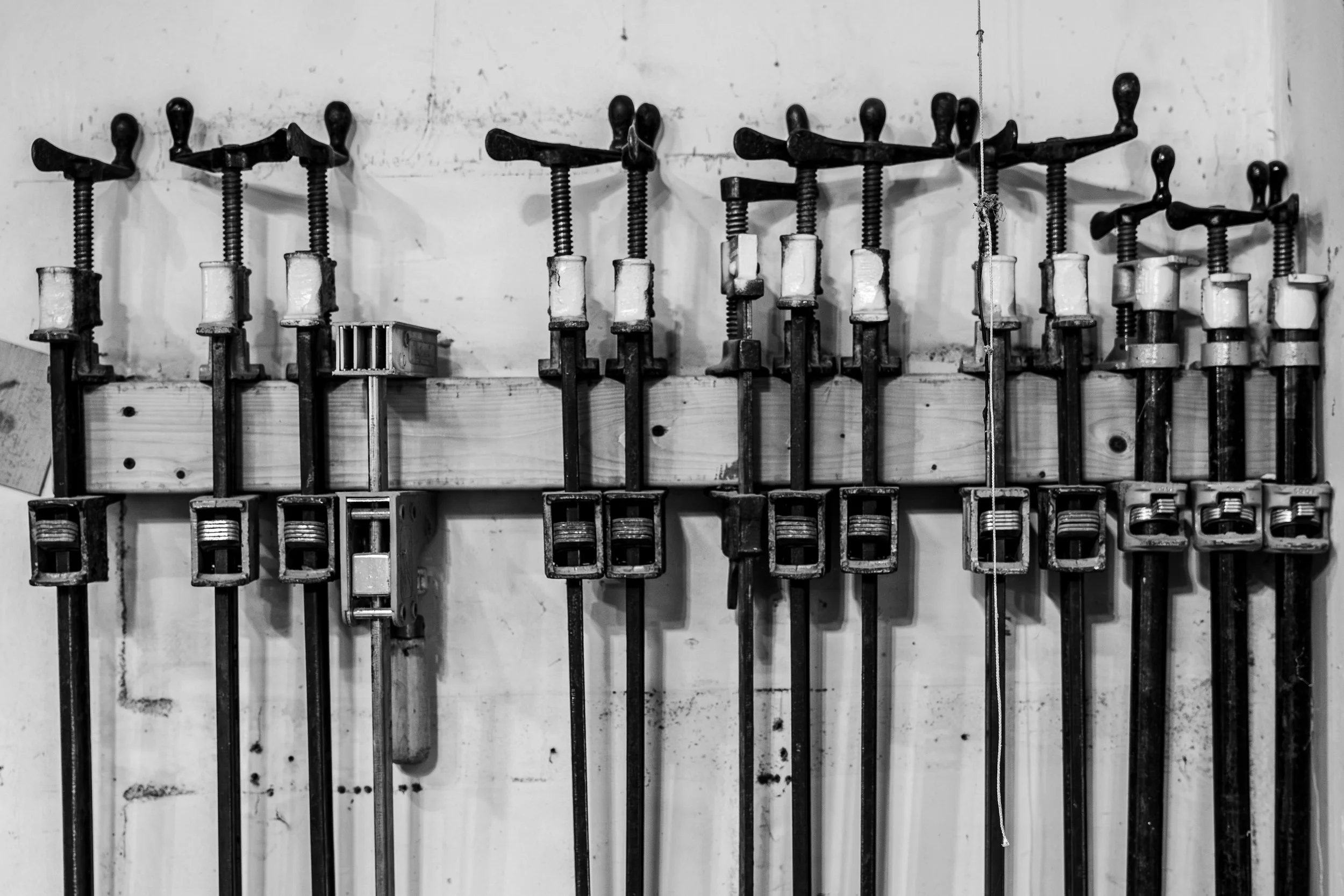

Recent work in Brent’s shop. © Brody Hartman

Purpose Defined

“For me, purpose is being in service,” Brent said. “It’s not about me or what I’ll receive, but if I am egoically balanced, I’ll receive greater gifts than I’ve ever imagined. To be in service is purpose for me.”

This understanding didn’t come quickly or easily. Brent described it as a journey, a long road of clearing the way. Through his work over the years—holding space for men, guiding boys through rites of passage, and, more recently, sitting with the dying—Brent’s sense of purpose has deepened into something embodied.

“It’s like there’s an alignment inside my soul when I’m in service,” he reflected. “And that alignment has shown me over and over again that purpose is about showing up for others in the most meaningful ways.”

Catching a reflection of Brent in one of his bespoke mirrors. © Brody Hartman

© Brody Hartman

Early Threads: Roots of Creativity and Generosity

Brent’s early life was shaped by creative inspiration and emotional complexity. His parents had him while in high school, and their youth brought challenges and unique dynamics to his upbringing. “I was an only child, raised by a mother, also an only child who had immense talent but lived under constant scrutiny and criticism from her own mother. She never realized her dreams—mostly because she chose to raise me over her work.” His father, a man of deep generosity, also left a profound imprint. “He’d give anything to help someone in need. If I told him someone’s family needed something, he’d be there.”

Art became a sanctuary for Brent, a space where he felt seen for the first time. "My high school art teacher, Millie Fraley, saved my life. One day, I walked into her class, and she was pushing a desk out of her office. I asked her what she was doing, and she said, ‘I’m making you a studio. Get in there and get to work.’ For almost two years, I had a room inside the art room that was mine. She saw something in me I didn’t see in myself."

That act of belief set Brent on a path toward creative expression and self-discovery. “She kept saying, ‘You’re going to college.’ I wasn’t so sure, but she made it happen. She was the first person who showed me the power of saying yes to someone else.”

“She was the first person who showed me the power of saying yes to someone else.”

Brent Skidmore in his woodworking shop. © Brody Hartman

Crossing a Threshold: Catching His Sons

Some of Brent’s most transformative moments came through fatherhood. He vividly remembers the births of his sons. “I was the first human hand to touch my boys as they came into this world. I remember trying to figure out what was happening inside me as I held them. I didn’t understand its magnitude at the time, but now I know there was calm and quiet in those moments that I didn’t experience anywhere else.”

Years later, that same feeling returned in an entirely different context. “Now, I sit with people in their last days and feel that same calm. It’s a quiet stillness. Maybe my whole journey has been about trying to feel that again, to be in that space where everything else disappears.”

Brent Skidmore ©Brody Hartman

The Height of Craft: Mastery, Recognition, and the Lie Within

Brent in is workshop. © Brody Hartman

After the birth of his sons, Brent’s career reached what many would call its peak. His work as a craftsman gained widespread recognition—his pieces were displayed at the Smithsonian Craft Show in Washington, DC, sold in galleries across the country, and commissioned by serious craft collectors.

Teaching has also been a profound source of fulfillment for Brent, allowing him to support students in discovering their voices and experiencing transformation through their work. For him, teaching is about creating spaces of collaboration and love where students can explore aspects of themselves that they may have never been able to express.

Reflecting on this role, Brent explained, “To stand adjacent to someone, teach them something that they can then realize themselves, in the same way people supported me, and help them realize their voice—and then see them actually transform by using materials, specifically wood—and have them experience something they’ve known of themselves but never been able to do; that’s what it’s about. It’s about building these spaces and communities and looking for ways of collaborating that allow people to experience their voice.” Reflecting on his roots, he shared, “Millie, my high school art teacher, said every teacher gets their one student. I got to be her one student. I feel like I’ve had the gift of multiple students. I’ve worked with students who are just incredible."

From the outside, Brent’s life seemed ideal. Yet, while teaching and craft brought moments of fulfillment, a deeper sense of discontent lingered beneath the surface. “I was a liar,” Brent admits. “I lied to myself, to my wife, to the people around me. I wasn’t living in integrity.” Despite the accolades, he couldn’t see his own value. His achievements felt hollow, unable to fill the void created by his lack of inner self-worth.

This inner struggle bled into his personal relationships. He was unable to find sustainable love in his life, and his marriage began to fracture under the weight of unresolved pain. Brent spent five years working to repair their relationship and rebuild trust, making meaningful changes in himself. Reflecting on that time, Brent shared, “At the end of five years, her truth was: ‘I’ve seen all the changes. I see all the work. And I don’t think I could ever trust or believe anything you say or do.’ The disconnect between who he was and who he longed to be left him feeling lost, even as he continued to succeed professionally.

Brent Skidmore ©Brody Hartman

Sometimes, Living or Dying is a Choice Away

“On April 12th, 2013, I tried to take myself out,” Brent recalls. “I was riding my bike down Town Mountain, screaming out loud in defiance, ‘Fuck you! I’ve got this!’ Then, out of the left side of my head, I heard a voice: ‘You should probably slow down. Today’s the day.’”

Woodworking clamps. © Brody Hartman

Brent ignored the voice. “I was flying down the mountain at 42 miles per hour when I hit water in the road. I locked my brakes, high-sided, and went flying through the air. I calculated as I fell: Am I going under this car? Between the first and second? Just before I hit the ground, I flipped upside down and I stared the driver in the eyes. I landed on the other side. I'm right handed. Now I'm crippled, essentially. I have 28 screws and four metal plates. just in this small section.”

Brent continues, “I once described it as being re-grafted to a different tree. That’s when I found MKP (Mankind Project), and I found these few dudes who showed up for me—strangers, by the way.

Brent’s double 13 tattoo marking a profound change in the direction of his life. © Brody Hartman.

That crash marked a moment of profound reckoning. Brent reflects on the disconnection that led to it. “I was separated from my spirit and my soul,” he says. “I know now that the voice I heard on the mountain was my divine self. But back then, I wasn’t listening.”

Although Brent had achieved external success, his deeper parts were in turmoil. “I didn’t like myself at all,” he admits. “Even the birth of my sons didn’t wake me up. Having a cancerous tumor removed on my 40th birthday didn’t wake me up. Those moments didn’t break through the deep lack of self-worth I carried.”

It was after the crash that Brent got a tattoo of the number 13—a reminder of the moment everything fell apart and began to shift. “There’s two 13s and it basically signifies the turnaround of living or dying. So now I live with all this purpose and service in this space in between the two.” The tattoo symbolized self-destruction and renewal, marking the point where Brent began rebuilding his life with intention and accountability. “It was about living or dying, and I chose to live.”

Can you build David’s casket?

Miscellaneous pattern templates. © Brody Hartman

Brent’s journey into working with the dying began during the pandemic. “My friend Tracy texted me out of nowhere and asked if I could build a casket for her partner, David.” David was a good friend of Brent’s, which made the experience even more personal and significant. He was dying of glioblastoma, and we hadn’t been in touch much, but I said yes immediately. There was no doubt in my mind.”

Building that casket was a profoundly personal and transformative act. “I spent two days alone in my studio. I played David’s playlist—music I didn’t like—but played it loud. I imagined their love surrounding me as I worked. I even sandwiched myself between them in spirit, trying to connect with something bigger than me.”

During David’s final days, Brent and two others took turns sitting vigil overnight. They divided the hours—one from midnight to 3 a.m., another from 3 a.m. to 6 a.m. These quiet hours created a unique connection. The small living room, already intimate, felt even more so with David present and his casket on the dining table. Because it was during the pandemic, most people attended the vigil virtually, which Brent found unsettling and profoundly different from what he now considers essential. For him, the overnight hours in the stillness and darkness have become the most sacred time to sit with someone who is dying.

“I watched what I call live grief happen. His two teenage children are there. They decorate the inside of his casket with mod podge, all these pictures on the inside of his box. Tracy tells me, there's no way my children could have done what they did, as far as grieving their dad without doing the casket and without anointing his body.”

Through David’s passing, Brent discovered a deeper understanding of service. “It wasn’t just about the casket—it was about being there, holding space, and witnessing the love and grief in the room. That was the moment I knew this work mattered in a profound way.”

Saying Yes to The Stranger

Not long after David’s death, Brent met Ethan, a young man dying of glioblastoma. Their connection was immediate and profound. “He showed up at my partner’s house with a giant scab on his head,” Brent said. “He was dying, but he was still living, too. There was something about his presence—it felt like God was in the room.”

Ethan’s cancer was aggressive, and he needed someone to help him navigate the difficult terrain of his final months. Brent couldn’t help but notice the uncanny connection between David and Ethan—both men had glioblastoma, a rare and devastating illness. That parallel deepened the weight and significance of his role in Ethan’s life.

Brent stepped in without hesitation, saying yes to being his companion, advocate, and support system. Reflecting on one of their early interactions, Brent recalled, “Ethan called me and said, ‘Can you take me to the hospital?’ He needed someone to speak for him when he couldn’t, and I said yes.”

Over the following months, Brent spent countless hours with Ethan, offering a steady presence amid uncertainty and pain.

"We spent 12 hours in the emergency room together. During that time, we got to know each other. It was literally a 12-hour conversation. And sometimes a 12-hour conversation with a medical person and me being the advocate. And what’s happening in that space—now I know, looking back—is that I’m becoming, anointed, it seems, to be something I’ve never been—to be service in a way I’ve never been in service."

As Ethan’s condition worsened, Brent remained by his side along with an extended community. He described the sacredness of sitting vigil with someone during their final days as an experience that profoundly shaped his understanding of service. Sitting vigil, especially in the quiet stillness of the night, revealed the profound power of presence—the act of simply being with someone without trying to fix or change anything. For Brent, these moments became sacred opportunities to offer love, trust, and connection. He saw this as an embodiment of grounded masculine energy—holding steady, calm strength in the midst of profound vulnerability.

“It was humbling to hold that space for him, to simply be there without trying to fix anything.”

Brent Skidmore ©Brody Hartman

Brent Skidmore © Brody Hartman

A Life in Alignment

Brent Skidmore © Brody Hartman

Brent reflects on his journey—from disconnection and lack of self-worth to one of purpose, meaning, and love. “It’s not complicated, but it didn’t come without pain,” he says. “There were people hurt along the way, including me, but I’ve come to understand something important: it still comes down to asking, ‘What does that little boy need? What do I need today?’”

I’ve found my peace. I no longer live in shame or guilt for what’s gone down. Instead, I trust the power of love to align everything.” Brent has also found a deep and nourishing love with his partner, Joanie. Their connection has been a source of healing and joy, grounding him as he continues his work.

"One person told me, ‘You’re on the bridge between the living and the dying.’ And I’ve come to see that as true. My work now is to communicate with both, to support both. It’s about creating alignment, even in the face of death, and finding a way to meet that moment with integrity and love."

Brent’s service isn’t about self-fulfillment. "It’s not selfless, and it’s not selfish. It’s just love. Only love prevails. When I say yes to others, I’m also saying yes to the divine in me. That’s where alignment lives. That’s where peace lives."

As he looks to the future, Brent holds a quiet hope: to continue this work, to meet others on the bridge, and to build something lasting—perhaps a conservation green burial site that fosters community and honors the sacredness of life and death.

“If I can impress upon people how much meaning and purpose can be found in their life if they say yes to a stranger. Brent tears up and continues, “I think it’s because I’m the stranger. Not in isolation, but I am the stranger. And everyone is, in a way. And no one is. That’s really the thing—no one is the stranger. So, if I put that label on someone and I said yes to them, in saying yes to them I see the potentiality of my understanding of the divine.”

Brent reflected in one of his bespoke mirrors. © Brody Hartman

Brent at the entrance to his workshop. © Brody Hartman

Brent near the entrance to his workshop. © Brody Hartman

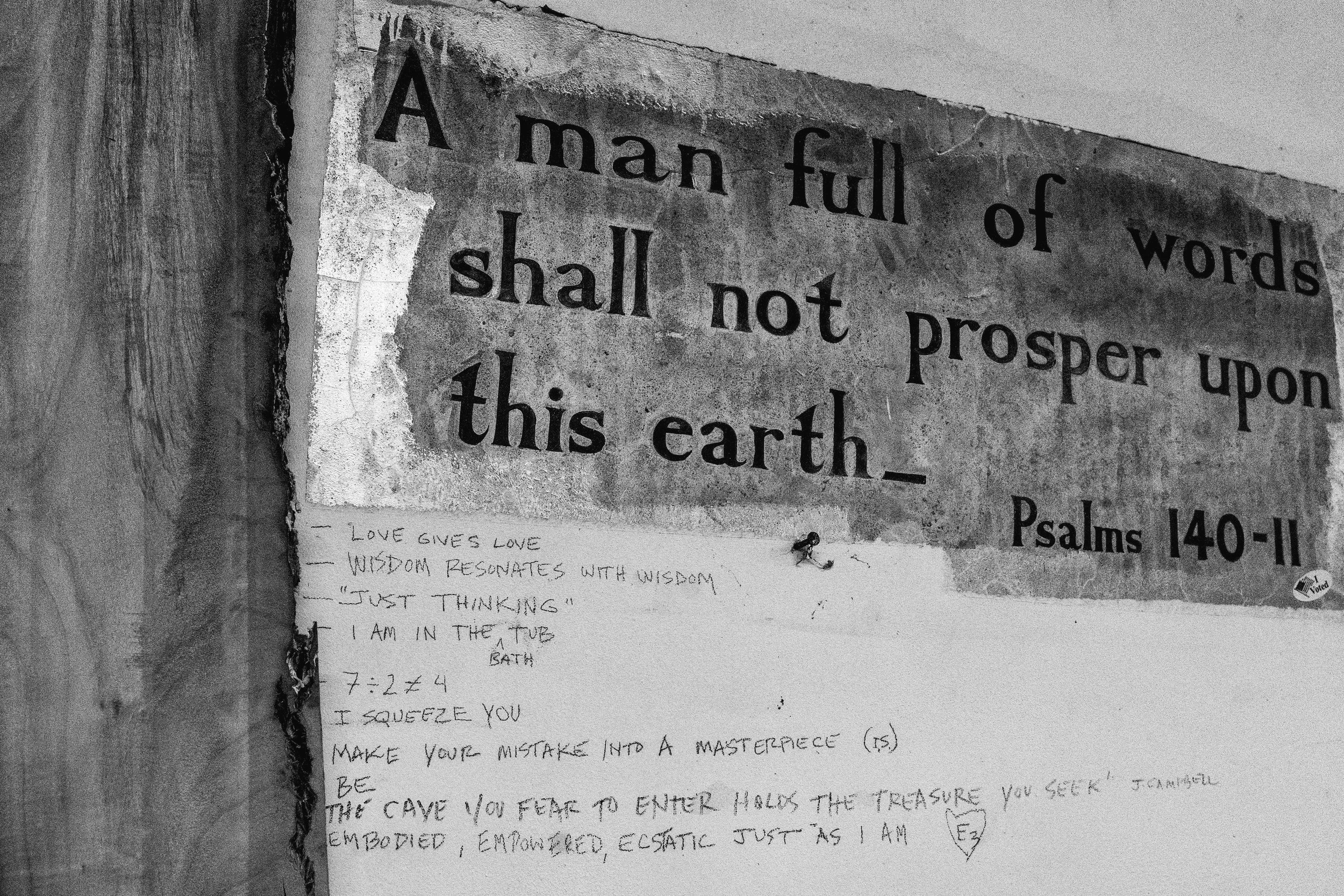

Brent inherited the Psalms excerpt when he took over the studio but added his commentary about life, love, and work. The last quote is a mantra offered by Ethan to his community as he was in the process of dying. ©Brody Hartman